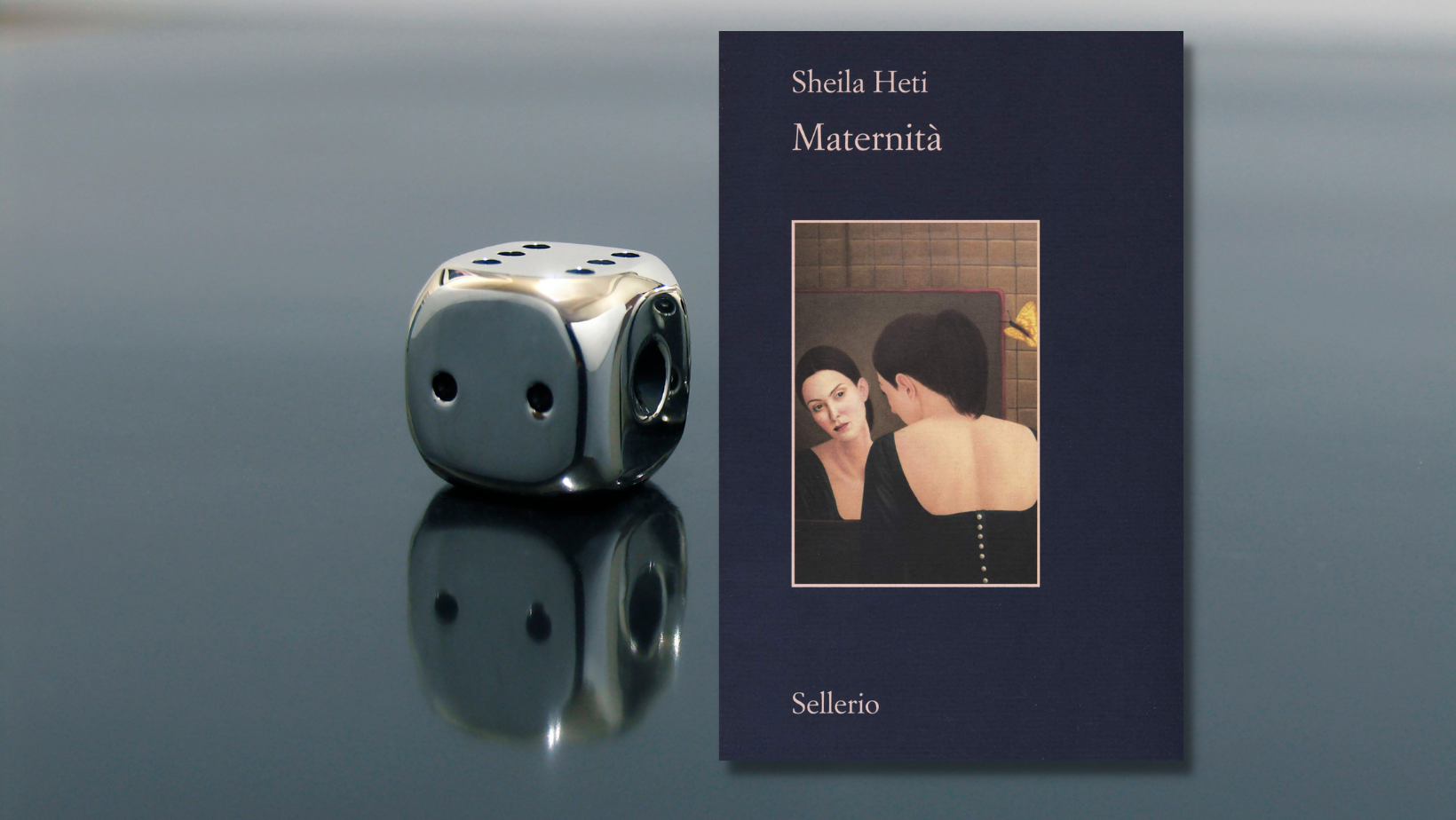

Motherhood by Sheila Heti. A review by Claudia Mazzilli

Sheila Heti talks about her struggle between duty and the refusal to procreate in the novel Motherhood.

In her novel Motherhood Sheila Heti, born in Toronto in 1976 from Hungarian Jewish parents, investigates without taboos all the possible causes that keep her from giving birth to a child.

This journal writing, while it carries out a daily exploration of oneself, is also a unique exercise of Socratic elenchus that tries to give birth, if not to a child, to the most authentic and hidden reason for not motherhood, in an oracular, sentimental and hilarious dialogue with chance. Sheila in fact interrogates three coins, inspired by the I Ching technique, a divination system born in China more than three thousand years ago. Fate answers her in its binary code of yes and no, almost giving a musical rhythm to the protagonist’s obstinacy to reach some certainty.

Is art a living thing – hile one is making it, that is? As living as anything else we call living?

yes

Is it as living when it is bound in a book or hung on the wall?

yes

So can a woman who makes books be let off the hook by the universe for not making the living thing we call babies?

yes

Sheila, close to forty, tries to figure out whether or not she wants children by asking her friends (as well as tossing the coins), most of whom advise her to have a child.

“What to do about these dangerous and beautiful sirens, like Mairon, whose songs, though irresistibly sweet, are no less sad than sweet? The term siren song refers to an appeal that is hard to resist, but that, if heeded, will bring the listener to a very bad end (…) And then resist like the monks who resist lying with women – no matter how good it would make them feel. Sing your songs more beautifully to yourself than the tempting mothers sing them”

“… with women our age, the first thing one always wants to know about another woman is whether she has children, and if she doesn’t, whether she is going to. It’s like a civil war: which side are you on? “

Another close friend, once pregnant, seems to push away and even exclude Sheila from her inner world “so there would be more room for her child to grow” .

Through mono thematic discussions about motherhood, Sheila puts her relationship with Miles to the test, arguing over the slightest thing with her partner (he already had a daughter from a previous relationship and would rather not have other children, “unless you really want it “). Miles in fact gives her good-natured, wise yet hilarious advice, having understood that Sheila has no maternal vocation:

“Finally, he was talking about how cultures have always held a places for those who don’t want children: in the clergy, priests, scholars and artists.”

“Waking up, I said to Miles, It might be nice to have a child. He said, I am sure it is also nice to get lobotomy.(…) He said, Two people who can help hundreds of people – that they should put their energies into one half-person, each? ”

“In the car ride home, Miles said, Of course, raising children is a lot of hard work, but I don’t see why it’s supposed to be so virtuous to do work that you created for yourself out of purely your own self-interest. It’s like someone digs a big hole in the middle of a busy intersection and then starts filling it up, and proclaims: Filling up this hole is the most important thing in the world I could be doing right now. “

Sheila does not fail to question fortune tellers and seers. And again: Sheila interprets dreams (dreams of an unborn child …, of a female Charon who guides her through the underworld geography of a subway …, dreams of flaccid breasts that each resembles a man’s penis, in a oscillation between the duty of female fertility and the aspiration to a freer male creativity, which can also be expressed in art and writing …). And then: she explores her moods and her wavering doubts (to have them or not to have them, these children?). According to the hormonal phases of the cycle, in chapters with recursive titles (Premenstrual Syndrome, Bleeding, Follicular, Ovulation). Sheila even undergoes all the medical checks necessary to freeze her eggs, in the event that in a few years she may change her mind, and when in the clinic she is told that her eggs are perfect “like fresh figs” she bursts into tears, because she doesn’t want children and she suspects that she will not want them even in a few years, and gets angry with nature that does not give her excuses for malformations or sterility. But it does not end here: everything must be explored in search of a cause; every structure of existence must be explored in an attempt to find an exact aetiology of one’s scarce or non-existent vocation to be a mother. The family history: a grandmother who could not complete her studies and was content to be a peddler of sweaters. A mother who instead redeemed her grandmother’s fate by becoming a doctor, but who, in order to fulfil herself in her study and profession, neglected Sheila, to the point of convincing her that a woman is either a mother or anything else (artist, professional …) and that the two together are not reconcilable. But Sheila’s search doesn’t stop with family history. It comes to retrace the tragic history of the short century: the Jews MUST have children, because otherwise they will give victory to the Nazis of the concentration camps who wanted them to be extinct. And then that recurring archetype: Jacob and his struggle with the demon-angel, indeed with God himself, and Jacob who obtains the blessing of the God with whom he struggled, whom he saw face to face, yet his life was saved. An archetype that has the epic gigantism of biblical characters and which nevertheless undergoes a slow and intimate resemanticization that will be revealed only in the finale.

Sheila also calls into question geopolitics:

“The egoism of childbearing is like the egoism of colonizing a country – both carry the wish of imprinting yourself on the world, and making it over with your values, and in your image.”

There is no lack of ecological explanations: it is not worth having children if the balance of the planet is compromised to the point that humanity risks extinction. Sheila also invokes evolutionary theories:

“Are my qualities of deceitfulness – which he pointed out I had, which he said all women had – part of the biological imperative? That in order to breed and raise children, morality has not to matter? The only thing that matters is the life of the child, while all other values are relative? Is that how my brain has developed over millennia? If I choose now – decide it, wasting no more time – not to have children, I set myself on a path of reforming my mind, making myself unable to lie and deceive… “

Or perhaps the problem is her vocation as a writer, who seeks eternity in the ancient, in dialogue with non-biological fathers and mothers (the authors of the past) rather than in the posterity of a real son.

The diary lasts three years; more than the game of coins, more than the talks (or “love meetings”, as Pasolini would have called them) with friends or with her companion Miles, with her mother and the fortune tellers or seers, writing claimed to be the most effective means , from which she confidently derive an answer: but the answer will come as natural as time, which gives her the increasingly peaceful perception of the end of her fertility, reconciling her with her partner, with her mother, with mothers (friends, colleagues, occasional acquaintances ), teaching her that the specific weight of motherhood and non-motherhood is no different on the scale. Time reconciles her with her free nature, unwilling to make irreversible choices (and a child is, there is no turning back): an open and curious nature but also inclined to close experiences that at some point may appear saturated and unsatisfying.

“It would be easier to have a child than do what I want. Yet when I so frequently do the opposite of what I want, what is one more thing? Why not go all the way into falsehood, for me? I might as well have kids. Yet that is where I draw the line. ”

“But the thought of having children always made me feel dizzy, or as elated as sucking helium, like all the things I rushed into, and just as impulsively, left.”

It may seem an absolutely banal conclusion, but every page of Sheila Heti is special, because without filters it reproduces a torment that so many women (perhaps every woman) feel when faced with the enigma of wanting / not wanting / having to be mothers, with a writing at times moving, at times enlightening, other times comically weepy, giving back to us, in a “true novel”, reflections that when they appear obvious are instead elusive, and when they touched one’s mind’s twists and turns suddenly offer straightforward and linear insights.