When the loneliness of mothers breeds monsters

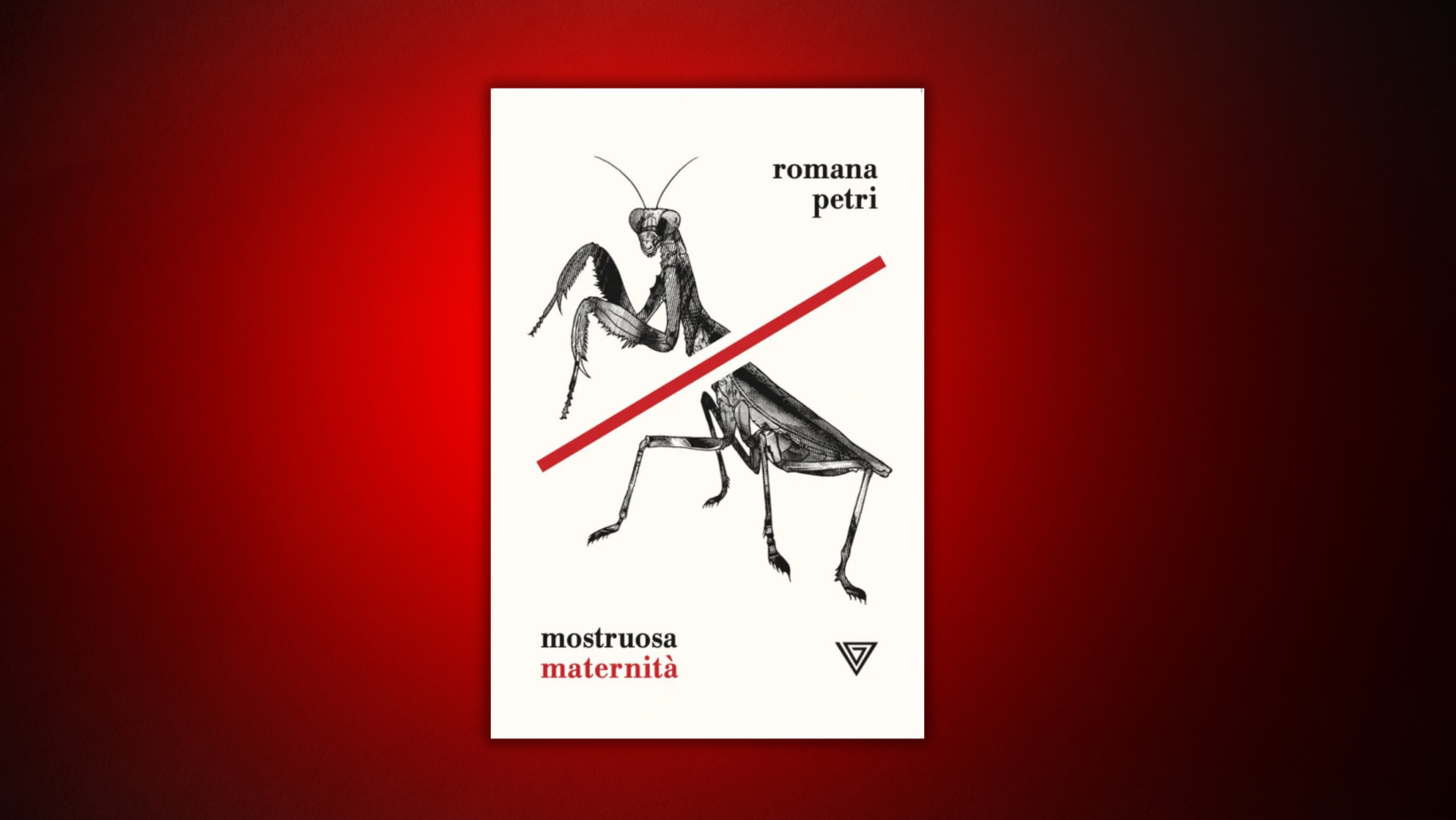

Romana Petri, Mostruosa maternità (Monstrous motherhood)

Review by Claudia Mazzilli

In Mostruosa maternità Romana Petri explores an impalpable border, the one where the ordinary, the destructive and the self-destructive merge, coexist and collide in the maternal: twelve murderous mothers, twelve women who give and then take away lives each in a different way, using their own hands or causing – more or less directly – a tragic death to sons or daughters.

Twelve short or longer stories, well assorted in terms of structure, in the choice of the narrating voice, in the time (from 1237 to the 2000s) and place they are set in (large cities such as Rome and Bologna, a glimpse in the life of the Italian province, but also Brazil, Yugoslavia, Latvia…), in style (now tinged with an archaic nuances, now very lively and colloquial, for example in the conversation between two clients at the hairdresser). In these twelve stories there are mothers who have been normal girls (those going out to a disco on Saturday nights), people from neorealist films (with their humble jobs, and perhaps a little ugly or not so young anymore), girls from East Europe immigrated to Italy, or authentic princesses, beautiful, rich and good, as in the fairy tales where the happy end is lacking. And for each one there is a blurred line between fairy tale and tragedy, between the illusion of happiness and the obituary, between the party and the short article in the crime news, between the dream of finding fulfillment through the love of a partner and the nightmare of the role of mother.

Their lives are marked by an irreversible transition to a condition that will imperceptibly take the contours of the pathological, of depression, self-harm, madness: bottled in a transparent glass, that of a role that has isolated and caged them instead of integrating and gratifying them through the status of mother, the protagonists realize too late that they no longer have a way out. They do not understand that now it is (dreadfully) something else completely: the stress of a sleep interrupted 17 times by a crying newborn, the fatigue of taking two hours to feed a baby who immediately throws everything up, the frustration for the dozens of kilos that have deformed a once perfect figure, or for the stretch marks that compromise potential modeling careers. Or the children to be cared for by giving up studies, trying to juggle between home and a self-managed work without the support of husbands or partners, not present and often avid missing partners not taking their own responsibilities. And then the disappointment, the worries and the obsessions for a child who is not normal, who has some form of disability.

But in these stories there is also the point of view of the daughters, their relationships with mothers and fathers, the envy of the mother for her beautiful and young daughter, or the jealousy of the mother when she discovers that the son prefers the father to her (yet the mother is everything!, the mother counts much more than the father!).

It is at this point that the monstrous emerges in the maternal, proving paradoxically very close to the caring, almost innate and intrinsic to it. And the monstrous is the jump from the tower, the bullet in the temple, the child drowned or torn to pieces. Or it’s choosing a violent partner who does what you dare not do.

No, it is not like a virus roaming in the air (says a fatalistic character in a story), it is not something that might happen or not, but alas, one breathes it and it is contagious. The monstrous is a destiny that at a certain point is fulfilled, which fatally had to be fulfilled according to an inescapable parable of events. Something before everyone’s eyes, but that no one deciphers until it explodes, and can act without hindrance and without remedy.

Framed by a prologue and an epilogue dedicated to the case of Annamaria Franzoni, the murderous mother who never confessed to infanticide (one of the cases of greatest media impact), the stories move between chronicle, fairy tale and popular legend, in a narrative perimeter variable between mainstream news, ancient saga and magical realism.

The mothers who kill are murderers, no doubt about it. But the writer knows how to put aside the judge’s hammer, how to lower the moralist’s index finger. Within the universal fairy tale of motherhood as the ultimate social realization and unique source of female happiness, Romana Petri gives voice and words to the women who in this myth discover the fraud of an exhausting endeavor in wealth as well as in poverty, the scandal of insomniac isolation both within normal families and in toxic relationships, the non-stop piling up of duties that lead to illness, to madness, to desire any end without the happy end.